With two high-profile trial settings coming up soon, Syngenta is inching closer to the heat of a public spotlight over allegations that its paraquat weed killer causes Parkinson’s disease. Thousands of people suffering from the dreaded, degenerative brain disease are suing the company, claiming it hid the risks of the chemical.

But Syngenta is working to dodge the light as long as it can.

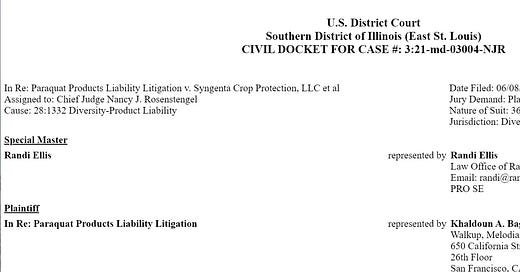

On Wednesday, Syngenta and lawyers for the plaintiffs in the case filed a flurry of pleadings in the multidistrict litigation (MDL) docket overseen by Chief Judge Nancy J. Rosenstengel within the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of Illinois.

A day earlier, Syngenta had asked the judge to allow the filings to be sealed from public view, and the judge agreed. So records that potentially carry great importance for public health are officially unavailable to the public.

Over the last several months, I have been fortunate enough to actually obtain and report on thousands of pages of internal Syngenta records that show an array of closely guarded secrets dating back decades about exactly what Syngenta officials have known about paraquat and Parkinson’s disease - and when they knew it. You can see the most recent story here or here.

Before the most recent story published, Syngenta asserted - erroneously - that the files were protected by court order and demanded that I destroy them, along with “any copies thereof, immediately and confirm in writing that you have done so…”

Needless to say, I did not destroy them and you can find many in a media library I’m building at The New Lede. (Any and all donations are much welcomed as we need a bigger, faster, better website!)

But there are many more records still buried beneath Syngenta’s claim of confidentiality that likely could help its customers, regulators and scientists better understand the risks carried by this particular pesticide.

Yes, it’s common practice for companies and courts to work hand in hand to keep corporate records away from the prying eyes of the public. But that does not make it right.

In 2019, my former employer, the international news outlet Reuters, reported what it called the “pervasive and deadly secrecy that shrouds product-liability cases in U.S. courts, enabled by judges who routinely allow the makers of those products to keep information pertinent to public health and safety under wraps.”

Because these types of cases often are settled before trial, company secrets can remain buried indefinitely, “robbing consumers of the chance to make informed choices and regulators of opportunities to improve safety,” as Reuters put it.

The Reuters investigation found that over the last 20 years, judges sealed evidence relevant to public health and safety in about half of the 115 biggest MDL defective-product cases, comprising nearly 250,000 individual death and injury lawsuits.

Every courthouse is a public space that is funded by, and created for the benefit of, we the people. When corporations use the courts to shield the truth, justice is perverted.

It’s time for the secrecy to stop.